16. Social Change, Renewal and Revolution

| Key Dates # |

|

|---|

| 1833 | William Wilberforce learns that legislation freeing slaves in the British Empire will pass through Parliament; he dies shortly afterwards

|

| 1820 | Beginnings of what became known as the (Plymouth) Brethren

|

| 1830 | Establishment of the Mormons, later re-named the "Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints"

|

| 1835 | George Muller establishes a faith-based orphanage in Bristol, England

|

| 1850 | Conversion of Charles Haddon Spurgeon, later called "The Prince of Preachers"

|

| 1859 | Darwin's "On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection" published

|

| 1854 | Doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of Mary

|

| 1865 | Beginnings of what became known as the Salvation Army

|

| 1870 | Vatican I, and the declaration of Papal Infallibility when speaking ex cathedra

|

| 1874 | "The Christian Doctrine of Justification and Reconciliation" by Albrecht Ritschl reduces Christianity to a social gospel

|

| 1882 | Friedrich Nietzsche's "God is dead" ("Gott ist tot") is first published

|

| 1885 | The Cambridge Seven, including CT Studd, arrive in China as missionaries

|

| 1886 | Karl Barth, Reformed theologian, considered the greatest Protestant theologian of the twentieth century and a major force against liberalism, born in Switzerland

|

Background

If the 19th Century was the greatest century for Christian missions and the impact of

evangelicalism on social standards in Europe (eg the abolition of slavery, focus on cleaning up

urban areas, better education, improvements in prisons), it was also the century during which

ideas born in the Enlightenment struggled for supremacy in people's thinking and belief systems.

The period was marked by astonishing political, economic and social changes, growth of empire,

rapid modernisation, industrial growth, expansion of cities (with the downsides of pollution and

growth of working poor, cf Charles Dickens, 1812-1870) and major scientific advances. But it

was also marked by a serious spiritual crisis. Central elements of the Christian message were

watered down. The Western "Christian" community was divided, between traditionalists and

those who embraced new religions, including the belief systems of rationalism, liberalism,

science without God and nationalism.

As the more radical implications of the scientific and cultural influences of the Enlightenment

began to be felt in the Protestant churches, "liberal" Christianity, exemplified especially by

numerous theologians in Germany, sought to bring the churches into the broad revolution that

modernism represented. In doing so, new ("critical") approaches to the Bible were developed,

new attitudes became evident about the role of religion in society, along with a new openness to

questioning the nearly universally accepted definitions of Christian orthodoxy.

In some parts of "Christian" Europe the church became increasingly alienated by political

movements, eg France, where the role of the Catholic Church in society gave way to the state.

The violent French Revolution failed and gave way to the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, whose

attempts at bringing all of Europe into a single Empire re-shaped politics and alliances across the

continent; his legacy was a nation that stumbled from one political system to another.

The United States experienced the most costly conflict of its history, a Civil War that ran from

1861 to 1865. Conflicts in Europe led to the creation of a united Germany and Italy. Germany

defeated France in a war in 1870. English interests (arguably saved in the 18th century from a

French style revolution by an evangelical spiritual and moral revolution) saw it involved in

conflicts in Africa and Asia. The power of the Pope in Italy diminished; at the same time the

church opposed political liberalism, liberal theology, rationalism and most Protestant efforts. A

Vatican Council (1869-1870, Vatican 1) led to the doctrine of Papal Infallibility in matters of

doctrine and practice when the Pope spoke "ex cathedra", ie in his office. However, this move

did not reconcile the church with modern thinking. The Roman Catholic Church was opposed by

Bismarck in Germany and other European leaders. At the same time, secular thinking was

leading away from Christian faith and the church was itself being undermined from within by

liberalism. Church in England declined in influence.

Liberal Christianity

Liberalism (also known as higher criticism, modernism, neo-orthodoxy, Bultmannism, new

hermeneutic) is a theological movement rooted in the early 19th century German

Enlightenment, notably in the philosophy of Immanuel Kant and the religious views of Friedrich

Schleiermacher. It is an attempt to incorporate modern thinking and developments, especially

in the sciences, into the Christian faith. Liberalism emphasizes ethics over doctrine and

experience over Scriptural authority. While essentially a 19th century movement, theological

liberalism came to dominate mainline churches in the early 20th century.

Protestant liberal thought in its most common forms emphasized the universal Fatherhood of

God, the brotherhood of man, the infinite value of the human soul, the example of Jesus, and

the establishment of the moral-ethical Kingdom of God on Earth.

Liberalism gave rise to other movements with varying emphases. Among these movements have

been the Social Gospel, theological Feminism and Liberation theology. One product of these

movements is the Myth of Christian Origins which denies the divinity of Christ and the authority

of the Bible. Many modern ministers and churches have been influenced by liberal claims that

evangelicalism is lacking in scholarship, unable to provide answers to secular humanism.

Some differences between evangelical and liberal theologies

| Evangelicals believe that... | Liberals believe that...

|

|---|

| There are absolutes, established by God; many things in the world are stable and fixed (Malachi 3:6a; Hebrews 13:8)

| Theology must not go beyond tentative assumptions; there are no absolutes.

|

| Conclusions can be reached in the field of theology that can be regarded as certain and final (John 14:6)

| It is unsafe to develop fixed views about God and theological views. Who/what is God? Who/what is truth?

|

| The Bible was written by men under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit; it is the infallible and inerrant Word of God (2 Peter 1:20-21).

| The Bible "contains" (or may not) the Word of God or words about God; it is just a book, written by men, full of errors, subject to investigation. The Old Testament is about Jews, for Jews.

Bishop Barnes: "The Old Testament is Jewish literature. In it are to be found folklore, defective history, half savage morality, obsolete forms of worship based on primitive and erroneous ideals of

the nature of God and crude science". The Bible is unreliable; the Gospels are inaccurate, inconsistent.

|

| Faith is the basic norm for the Christian life (Hebrews 11:6).

| Any modern man or women who honestly faces all

the recent scientific discoveries can no longer

accept the supernatural elements of Christianity.

"Faith" does not need any historical or objective

support because it is existential".

|

| Modern man must adjust to the Bible.

| The Bible must adjust to modern man. The Bible is a human document, written to inspire religious experiences. We are free to interpret it as we wish and decide what we want to keep/exclude.

|

| The answer to our problems is for man to be reconciled to God through Jesus Christ.

| The answer to our problem is man's reconciliation with man.

|

| All men are sinners.

| Beliefs in doctrines such as original sin offend modern sensibilities.

|

| Jesus Christ was both human and divine, the Son of God.

| Jesus' divinity was invented by religious writers. The so-called miracles of the Bible should be seen as statements of belief, not literally; it has out-of-date stories, concepts and values.

|

| The death of Christ paid for the sins of the world.

| Notions of sin and sacrifice are Greek/Jewish ideas that must be reinterpreted for modern times. We need to avoid "butcher shop religion".

|

Results of liberalism are: confusion re belief; selectivity (people take what they want and reject

the rest); declining church attendance; naturalism; growth of cults; moral void and relativism

("no one can tell me what to believe in or how to live"); religion that has form but no power;

irrelevancy (why both with Christianity?) and death of hope.

Liberal theology continues to challenge Biblical theology in our day.

Emergence of Alternative Sects/Cults

- Unitarians (modern-day Gnostics, from the 1770s)

- Mormons/Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (modern-day Pelagians, from the 1820s, officially established in 1830)

- Jehovah's Witnesses (modern-day Arians; from the 1870s)

- Christian Science (modern day Gnostics and Docetists, along with Unitarians, also from the 1870s)

These cults (and others like them) preach "a different Jesus, a different Gospel, a different Holy

Spirit" (2 Corinthians 11:4; 1 John 4:3). They believe they are "the only true church", with the

only genuine revelation ("I am the only man that has ever been able to keep a whole church

together since the days of Adam", Joseph Smith), reject mainstream Christianity.

Revolutions

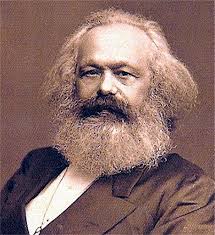

Anti-Christian Communism was openly hostile to religion. Karl Marx condemned religion as the

"opium of the people" as he considered it created a false sense of hope in an afterlife that held

people back from facing their economic and political circumstances. This was echoed by Lenin,

who believed that religion was used by ruling classes as a tool of suppression of the people.

Marxist-Leninist governments in the 20th century were generally atheistic. All of them

restricted the exercise of religion to a greater or lesser degree. Albania actually banned religion

and officially declared itself to be an atheistic state.

In Latin America, a succession of anti-clerical regimes came to power beginning in the 1830s.

The confiscation of Church properties and restrictions on people's religious freedoms generally

accompanied secularist, and later, Marxist-leaning, governmental reforms. One such regime

emerged in Mexico in 1860. Church properties were confiscated and civil and political rights

were denied to religious orders and the clergy. More severe laws called "Calles Law", during the

rule of atheist Plutarco Elías Calles, eventually led to the worst guerrilla war in Latin American

history, the Cristero War. In spite of these challenges, the Catholic Church was the dominant

religious force throughout Latin America.

The Church in Russia

The Orthodox Church has been in decline since the Great Schism of 1054. However, there have

been some notable leaders. Cyril Lucaris (1572-1638) formulated a Confession of Faith in 1629.

It was Calvinistic and emphasised predestination, the mediatorial work of Christ and justification

by faith alone. Like the church in the West, organised Russian Orthodoxy was usually closely

linked to the political establishment.

By the end of the 17th century there were Protestant churches in Russia, although most of their

adherents were not Russians; for example a church in Moscow comprised German merchants who

resided in that city. When Nikon became patriarch of Moscow in 1652 Russia was flourishing and

increasing in political power and was thought to be a third "Rome" and should lead the Orthodox

Church.

Peter Mogolia (1596-1646) gave the Kiev school a stability that it lacked previously. He was an

able scholar who studied and was thoroughly familiar with the Latin scholastics. His work,

Orthodox Confession of the Catholic and Apostolic Eastern Church, was accepted by the

patriarchs of Constantinople, Jerusalem, Alexandria and Antioch and became a major work in

the East.

The Russian Orthodox Church held a privileged position in the Russian Empire, expressed in the

motto Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Populism, of the late Russian Empire. It was officially placed

under the control of the Tsar by the Church Reform of Peter I in the 18th century. Its governing

body was the Most Holy Synod, which was run by an official (titled Ober-Procurator) appointed

by the Tsar. The church was involved in campaigns of Russification, and accused of involvement

in anti-Jewish pogroms (many Russian Orthodox clerics, including senior hierarchs, openly

defended persecuted Jews). The church, like the Tsarist state, was seen as an enemy of the

people by the Bolsheviks and other Russian revolutionaries. During the Soviet period it was

quashed, but re-emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union and is flourishing today.

Some Influential People During This Period

1. Christian

CH Spurgeon (1834-1893)

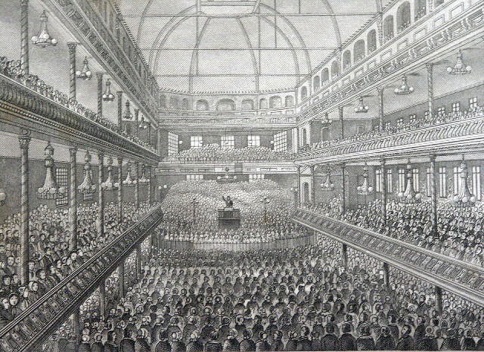

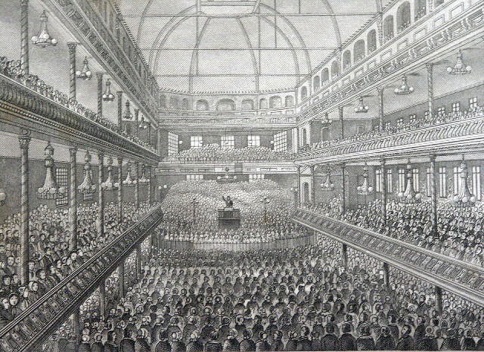

Charles Haddon Spurgeon was England's best-known preacher for most of the second half of the

nineteenth century. In 1854, just four years after his conversion, Spurgeon (then only 20),

became pastor of London's New Park Street Church (formerly pastored by a famous Baptist

theologian named John Gill). The congregation quickly outgrew their building, moved to Exeter

Hall, then to Surrey Music Hall. Spurgeon frequently preached to audiences numbering more

than 10,000 - in the days before electronic amplification. In 1861 the congregation moved

permanently to the newly constructed Metropolitan Tabernacle. Spurgeon's printed works are

voluminous; most are still in print.

Dwight L Moody (1837-1899)

Prominent American evangelist who set the pattern for later evangelism in large cities.

Moody left home at 17 and grew up in Boston. He was converted from Unitarianism to

evangelicalism. In 1856 he moved to Chicago, working as a shoe salesman. In 1860 he gave up

business for Christian ministry. He worked with the Young Men's Christian Association (1861-73),

was president of the Chicago YMCA, founded the Moody Church and engaged in slum missions.

In 1870 he met Ira D Sankey, a hymn writer. They made extended evangelical tours in Great

Britain (1873-75, 1881-84). Moody opposed divisive sectarian doctrines, deplored "higher

criticism" of the Bible, the Social Gospel movement, and the theory of evolution. Instead he

colourfully and intensely preached "the old-fashioned gospel," emphasizing a literal

interpretation of the Bible and looking toward the premillennial Second Coming. His mass

evangelism campaigns were financed by prominent businessmen who believed he could help

alleviate the hardships of the poor. Moody ardently supported various charities but felt that

social problems could be solved only by the work of Christ changing people. As well as

conducting evangelical campaigns, he organised annual Bible conferences in the USA. In 1889 he

founded the Chicago Bible Institute (now the Moody Bible Institute).

William Booth (1829-1912) and the Salvation Army

The Salvation Army began in 1865 when William Booth, a London minister, gave up the comfort

of his pulpit and decided to take his message into the streets where it would reach the poor, the

homeless, the hungry and the destitute (the London Dickens wrote about). His original aim was

to send converts to established churches of the day, but soon he realized that the poor did not

feel comfortable or welcome in the pews of most of the churches and chapels of Victorian

England. Regular churchgoers were appalled when newly converted, poorly dressed, unwashed

people came to join them in worship. Booth decided to found a church especially for them - the

East London Christian Mission. The mission adopted military forms of organisation, to ensure it

was able to cope with the often chaotic circumstances in which it ministered) and was re-named

(by Booth) the Salvation Army.

John Nelson Darby (1800-1882) and the Brethren

Many Christians in Britain had similar concerns about the established church. Churches holding

orthodox doctrines tended to coldness. Liberal churches were dead. Under the leadership of

Anthony Norris Groves, a group simply called "the Brethren" was formed. It was their intent to

reject denominationalism and ecclesiastical tradition. The Holy Spirit must lead worship. The

Bible must be central. The believer's life must be Christ-centred. Darby joined this group and

became its most influential leader. Their main congregation met in Plymouth (in the south of

England) and became known as "Plymouth Brethren."

The Brethren emphasized the unity of believers and were interdenominational. Communion was

to be simple and served by different individuals each week. There were few full-time pastors,

since all members were called to be priests and were meant to be as responsible for the church

as their abilities permitted. Darby interpreted the Bible as representing different eras, or

"dispensations", of God's grace. Some passages spoke of Israel, others of the church. His view

is familiar to many Christians today, for it became the basis of Scofield's Reference Bible. One of

the key emphases of the Brethren was the Second Coming of Christ, neglected at that time.

Darby taught that Christ would come for the church before the Great Tribulation. This view was

controversial at the time because it lacked historical roots. The Plymouth Brethren were

missionary-minded. Darby helped complete a new translation the Old Testament into German.

Led by Darby, who considered established churches corrupt, a group of Brethren known as

Darbyites became exclusive and formed their own congregations, with few dealings with outside

churches (this remains the case). Darby was criticised by Spurgeon for limiting the Gospel.

2. Non-Christian

Charles Darwin (1809-1882)

Darwin was a British scientist who laid the foundations of the theory of evolution and

transformed the way many people think about the natural world.

Darwin himself initially planned to follow a medical career, and studied at Edinburgh University

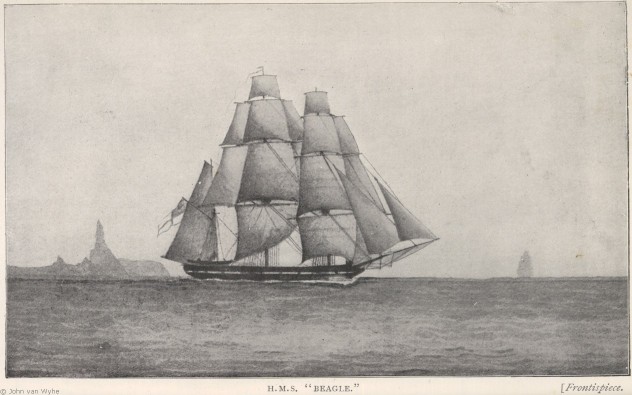

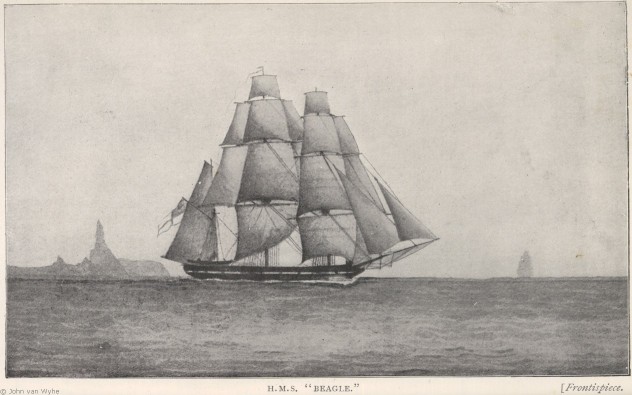

but later switched to divinity at Cambridge. In 1831, he joined a five year scientific expedition

on the survey ship HMS Beagle. At this time, most Europeans believed that the world was

created by God in seven days as described in the Bible. On the voyage, Darwin read Lyell's

'Principles of Geology' which suggested that the fossils found in rocks were actually evidence of

animals that had lived many thousands or millions of years ago. Lyell's argument was reinforced

in Darwin's mind by the variety of animal life and the geological features he saw during his

voyage. In the Galapagos Islands, 500 miles west of Ecuador, Darwin noticed that each island

supported its own form of finch which were closely related but differed in important ways.

On his return to England in 1836, Darwin tried to solve the riddles of his observations and the

puzzle of how species change. He proposed a theory of evolution occurring by a process of

"natural selection", ie animals/plants best suited to their environment are more likely to survive

and reproduce, passing on characteristics that help them do so to their offspring. Gradually, the

species changes over time. Darwin's overall conclusions rejected the Biblical creation account.

Darwin worked on his theory for 20 years. After learning that another naturalist, Alfred Wallace,

had developed similar ideas, the two announced their conclusions in 1858. In 1859 Darwin

published 'On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection'. The book was extremely

controversial, because the extension of his theory was that man was simply another form of

animal. It made it seem possible that even people might just have evolved - quite possibly from

apes - challenging the prevailing belief about how the world was created. That controversy

continues today.

Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855)

Danish philosopher, theologian, poet and social critic. Kierkegaard thought of himself as a man

destined to make Christianity difficult.

Kierkegaard is known as the founder of modern existentialism: "a philosophical theory or

approach which emphasizes the existence of the individual person as a free and responsible

agent determining their own development through acts of the will". He divided the "Christian

life" into three stages - the aesthetic, the ethical and the faithful. The aesthetic life is the man

who is down in the dumps and cares nothing for life. The ethical man attempts at reforming his

life with law and discipline. But the man of faith attempts to make a "leap of faith" to trust in

what his destiny may dictate to him as a Christian walk with God. This last religious stage can

only be reached by a conscious understanding of sin and leap towards God's mercy for the

person, although there are no guarantees that God will be merciful.

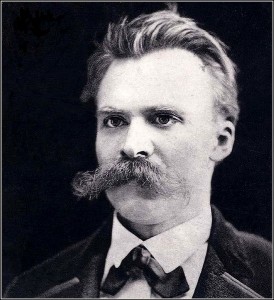

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

Nietzsche studied theology and classical philology at the University of Bonn and later philology

at the University of Leipzig. A meteoric academic rise saw him appointed as a professor at the

University of Basel at the age of 24.

Nietzsche argued that the Christian system of faith and worship is harmful to society because it

allows the weak to rule the strong. In effect, he contended, it suppresses the will to power

which is the driving force of human character. Nietzsche wanted people to reject Christian

morality and become "supermen", while harbouring fears that, without God, the future of

mankind could spiral into a society of nihilism. His answer was for man to find new values,

meaning and morality in the absence of god, themes that he was to address in Thus Spake

Zarathustra (1883-92), Beyond Good and Evil (1886), The Birth of Tragedy (1872).

Nietzsche is known for his declaration that "God is dead". The idea is stated in "The Madman":

"God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. Yet his shadow still looms.

How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and

mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who

will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals

of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this

deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?"

Karl Heinrich Marx (1818-1883)

Marx was a Jewish German revolutionary, sociologist, historian and economist. He published

(with Friedrich Engels) Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei (1848), commonly known as The

Communist Manifesto, the most celebrated pamphlet in the history of the socialist movement.

He also was the author of the movement's most important book, Das Kapital. These writings

and others by Marx and Engels form the basis of (anti-"capitalist", anti-Christian) Marxism.

Approaching the 20th Century

As the 19th Century ended there were unprecedented opportunities, and challenges to all forms

of faith and theology. Many assumptions would be tested in "our" 20th Century. Belief would be

re-defined or re-discovered. The key to the way forward would be understanding what we

believe, and why, and how it matches God's plan and purposes in the modern world.

Additional Reading

Blainey, G, A Short History of Christianity, Viking, Melbourne, 2011

Hong, HV and Hong EH, The Essential Kierkegaard, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1995

Lion, A Lion Handbook, 1990, The History of Christianity

Miller, A, Miller's Church History: From the First to the Twentieth Century

Spurgeon, CH, Lectures to My Students, Marshall, Morgan and Scott, London, 1973, var. editions

Spurgeon, CH, The Treasury of David: An Exposition and Devotional Commentary on the Psalms, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1978, various other editions

Renwick, AM, The Story of the Church, Intervarsity Press, Edinburgh, 1973